About my new song – coming March 11!

Out of many, one.

John Kay, artist (1742-1826), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Me, approximately age 6: “Dad, what does ‘e plurib…’ this, on the dollar bill, mean?” If you’ve ever met my father you know you’ll always get far more than just the answer you were looking for. That particular day I heard that it was an early motto of the country we both happened to be born in, but not the official motto. That was also printed on our money: “In God we trust,” which I’m certain he followed, as ever, with, “…all others pay cash.”

Hope and promise — the stuff of song

I was raised to believe that E Pluribus Unum meant something more than its translation. It was an expression of hope, a promise to become whole — and better than what had come before.

Not that it perfectly described reality. It clearly did not. American liberty did not extend to everyone in 1776, nor in 1876, not in 1965, ’84… in fact, it never has. But it named an aspiration: out of many, one. Not sameness. Not uniformity. Unity.

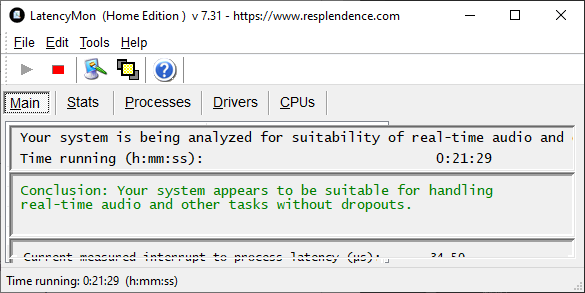

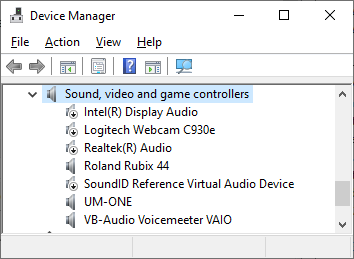

That aspiration fascinated me that day, and filled me with hope, long before I wrote any song — half a lifetime, to be precise; I wrote my first two songs at age 9! I’ve written many songs since, and though many years later it remains a fact that few have heard them, I continue writing. It’s now the 21st century, and though I don’t have a flying car, like George Jetson, I have a digital audio workstation (DAW). I’m learning how to fly.

My newest song, “E Pluribus Unity – Diversity is Strength” began, musically and lyrically, at a cosmic scale. The verses step back from our self-importance entirely. They consider the age of the Earth, the span of human history, the size of the Milky Way. Against 13.8 billion years, our ideological quarrels are microscopic. Against the breadth of a galaxy, our tribal anxieties seem almost fragile. And yet — within our brief span — we often allow them to matter immensely.

To begin again

It is possible to hold both thoughts at once: that we are cosmically small, and morally consequential. That tension led me back to 1776. When Thomas Paine published Common Sense, he was not writing from a position of comfort. The outcome of the American experiment was far from certain. Fear was not irrational; it was pervasive. Empire was powerful. Independence was dangerous. And yet Paine wrote:

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

I adapted portions of that passage for the bridge of this song — compressing, omitting, reshaping — trying to preserve its force within a fourteen-bar section. The line that stayed with me most was this idea of beginning again. Not perfecting the old world. Not retreating into it. Beginning anew.

Paine’s rhetoric was not gentle. In The Crisis he went further, naming fear as the foundation of reaction, even writing: “Every Tory is a coward; for servile, slavish, self-interested fear is the foundation of Toryism…” Eighteenth-century polemic was not subtle!

To be governed by fear, or by vision?

Beneath the invective was a psychological claim: that contraction, exclusion, and smallness are often rooted in fear. Paine believed the revolutionary project required courage — not merely military courage, but imaginative courage.

Every era confronts the question: will fear govern us, or will vision? The theme feels contemporary without being partisan.

Theme to music

For the songwriters and musicians who may be reading, while everything I’ve ever done begins with improvisation, when I’m with it, the DAW lets me capture much I once let get away. I thought this one out: the verses and chorus live in A Major — grounded, stable, almost luminous. In the bridge, the harmony shifts abruptly into C Mixolydian. There is no careful preparation. The floor moves. The tonal center relocates. It destabilizes before it resolves. That move was not accidental.

Revolutions — personal or political — rarely arrive politely. They interrupt. They displace. They challenge the security of what felt settled.

And then, if they are to endure, they must integrate. The harmony finds its way home again — not unchanged, but clarified. The guitars and the Mini Moog trade phrases like a small ensemble arguing toward coherence, and before the conversation ends they speak in unison.

Out of many voices, one line.

That unison is not uniformity. The timbres remain distinct. The instruments do not become each other. But they converge.

I am under no illusion about the historical contradictions embedded in the founding era. The rhetoric of liberty coexisted with slavery, dispossession, and exclusion. The American story has always been morally unfinished.

But I was raised to believe that the aspiration itself — the expansive language of equality and shared destiny — matters. That the ideal exerts pressure on the reality. That it calls nations and humanity forward rather than to fall backward.

The dream is over

John Lennon

What can I say?

The dream is over

Yesterday

I was the dream weaver

But now I’m reborn

I was the Walrus

But now I’m John

And so, dear friends

You’ll just have to carry on…

So dear friends, shall we carry on?

The question, nearly 250 years later, is not whether the experiment was flawed. It was. The question is whether we still believe in expansion rather than contraction. Whether diversity is a threat to be managed or a strength to be woven into unity.

Against the scale of the universe, our fears are small. But within the narrow bandwidth of our lives, they can shape everything.

Paine believed ordinary people possessed the power to reimagine their political world. He believed imagination was not naive — it was necessary.

The universe is larger now than he knew. We are smaller within it than we once imagined. And yet his assertion remains unsettling:

We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand, and a race of men, perhaps as numerous as all Europe contains, are to receive their portion of freedom from the events of a few months. The reflection is awful, and in this point of view, how trifling, how ridiculous, do the little paltry cavilings of a few weak or interested men appear, when weighed against the business of a world.”

— Thomas Paine (1776), Appendix to Common Sense

That line does not belong to 1776 alone. It belongs to any generation willing to claim it.

My newest song, “E Pluribus Unity – Diversity is Strength” will drop March 11.

§

E Pluribus Unity – Diversity is Strength

Verse

Have you contemplated the age of our Mother Earth?

And all the life that grew before we appeared

Paved our way to birth?

Have you not considered the size of the Milky Way?

Have you stood in the eye of the hurricane and

Counted stars that way?

Chorus

Diversity is strength

Equity means fairness

Inclusion builds community

Awakening awareness

Dignity, respect

Or simply say “good manners”

Each culture has its Golden Rule

Let’s build a better world

Verse

Have you anticipated A time when we all can be free

To live and love without facing judgement

For whom we’ve come to be?

Bridge

[The birthday of a new world ]

We have it in our power to begin the world again…

[How trifling, how ridiculous … ]

The little paltry cavilings of a few weak … men appear,

when weighed against the business of a world.”

Choruses out

Diversity is strength

Equity means fairness

Inclusion builds community

Awake in bright awareness

Dignity, respect

And mutu’l understanding

Each culture has its Golden Rule

Let’s build a better world

© Word & Music 2026 Richard Fouchaux/GuitarFaces Music All rights reserved